The food and beverage industry is a booming one because, let’s face it, people need to eat. It is reported that food consumption in Malaysia has been growing at a rapid rate since the year 2000. Not only that, but with hankerings for different foods to suit different moods and palates becoming more and more discerning, competition in this industry is fierce. Those who venture into the restaurant or food and beverage business – doing so out of a passion for food or as an entrepreneurial adventure – find that they are faced with many challenges that they may or may not anticipate, be it in the kitchen, or relating to finances, supplies, employees, décor, daily operations and so on, in addition to the pressure from market competitors.

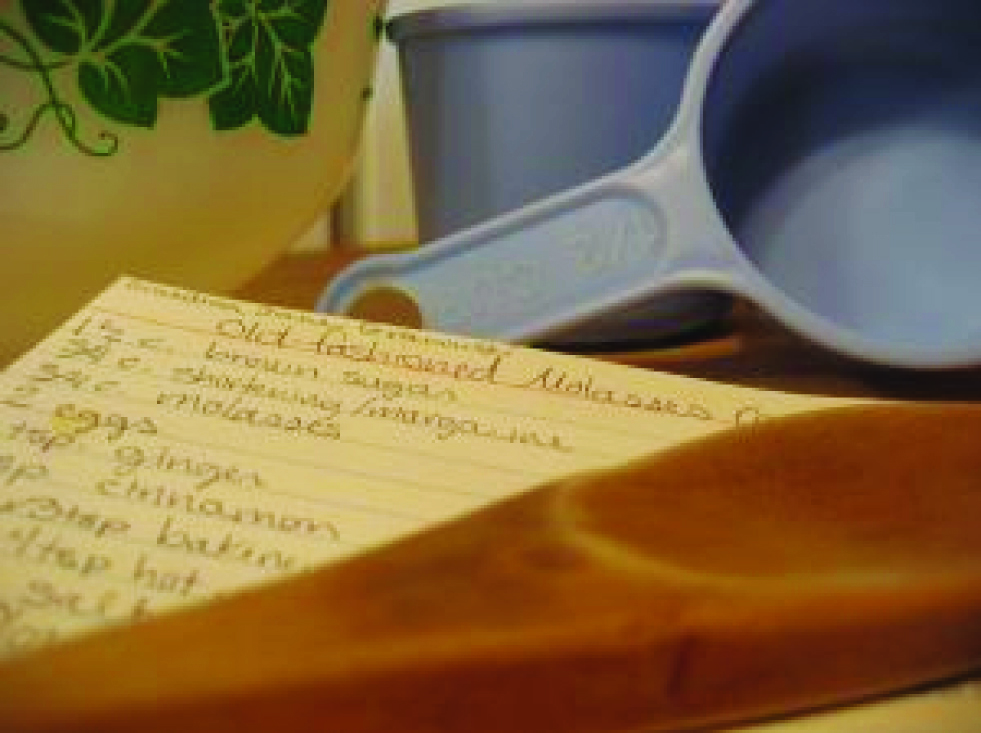

When dining out, for example, there are several things that attract people to a particular restaurant and not others. Besides parking facilities, it could be a catchy name, the interior decoration (e.g., furniture, display items on the wall), menu with fancy sounding items, uniquely designed cutlery and plates, the uniforms of the restaurant staff, popularity of the chef, or a number of other things. While there are many aspects of the food and beverage industry that are important, we will address one fundamental factor that entices people by creating a delicious and memorable taste experience that keeps them coming back for more – the recipe.

Special and good recipes are the unique selling point of most restaurants. As with all unique selling points, they should be protected from being copied or used by others. So how does one intending to produce food products on an industrial scale protect their special recipe and maximise their ownership rights to the recipe?

The recipe itself (that being the list of ingredients and the method of cooking used to combine the ingredients) can be protected by way of patents, if and only if, the recipe is new. This means that no equal recipe should have been published before or used before worldwide and the owner of the recipe has not revealed the ingredients and the method to produce the special food item to anyone on a non-confidential basis.

Once the patent application is made and the Patent Examiner is satisfied that the subject matter is new and inventive, then the patent for the recipe will be granted (in the country for which the patent was applied). A granted patent will provide the owner a twenty year period to exploit their patent. After the twenty year period expires, any member of the public can reproduce the recipe for their use. This means that the recipe has been donated to the public after the patent expires (as the public can refer to the patent documents for the composition of the recipe and the method of making the product using the composition).

An abstract of a patent for a recipe applied for in the US by an individual is shown below, together with one of the schedules for ingredients and flow chart for the steps involved in the process:

The patent shown is for a garlic sauce and a method of preparing the sauce. The owner is a company – Mamo’s Corporation – that filed their patent in 1996. Mamo’s Corp owns exclusive rights to the patent for the garlic sauce up to 2016. They can license their patent rights to sauce manufacturers or restaurants and earn passive royalty income. Alternatively they can manufacture and sell the sauce at a premium price, in hypermarkets, supermarkets, small grocery shops and even to restaurants.

Although patent protection has its advantages, many individuals and companies choose not to patent their recipe as patent protection has a limitation, in that the owner of the recipe can only exploit the recipe for 20 years. Instead, owners of recipes prefer to rely on the protection afforded by keeping the recipe as a “trade secret”. Trade secrets are information that is kept confidential (i.e., kept as a secret and not readily accessible to individuals in the company, apart from those that need to know the information to carry out the recipe) because they have commercial value.

Reasonable steps must be taken by the owner of the information to keep it secret (i.e., through confidentiality agreements with employees, non disclosure agreements with third parties, etc). Should there be unauthorised use of the trade secret by a third party, the owner of the trade secret can claim damages and costs in Court.

Examples of well known trade secrets include the formula for Coca-Cola and Colonel Sanders’ recipe for fried chicken.

There is no registration system for a trade secret. However, it is risky to rely on trade secrets because the protection fails if the recipe can be “reversed engineered”. In other words, the protection is ineffective if the composition can be figured out once someone tastes the food item and experiments with the method of making the food item. Where the recipe can easily be ascertained, trade secrets would not be the right protection.

With regard to both types of protection for recipes mentioned earlier, the need for the recipe to remain new and confidential is paramount. Unless the recipe was revealed on a confidential basis (there must be proof to substantiate this), the recipe will no longer be considered “new” (a criteria required for patent protection) nor will it be considered a “secret” (a criteria required for “trade secrets”).

If this is the case, then the owner of the recipe would be advised to start packaging the food item in a unique manner and use a unique name for the food item. This unique name will serve as a trademark for the food item and the food item can be sold to consumers or to restaurants for a profit. In this scenario, the owner would own the copyright and/or industrial design to the unique packaging of the product and the trademark applied to the food item.

Some examples of the use of trademarks on food items with special recipes are those used on pre-packed sauces. In Malaysia, there are Maggi sauces, Lee Kum Kee sauces and Lingham’s sauces, among many others used in the food and beverage industry. As for examples of product packaging registered as an industrial design, here are a few:

In a nutshell, recipes can be protected by various intellectual property rights, while the food products that result from the recipes can be named and packaged in a unique, distinctive manner and protected from copying. When all these rights have been identified and protected, the owner of the recipe is then free to commercialise the recipe and maximise its revenues, with assurance that any copycats will be sued for their unlawful acts.